When the stream of consciousness technique was first introduced at the turn of the 20th century, it was difficult for many publishers to accept it. Mainly because, such a style endorsed ungrammatical choppy sentences and sentences that had not made much sense. After James Joyce, finished and published Ulysses, it was almost impossible to comprehend it, because of the many spelling and grammar errors in it: mother was spelt as nother and many such errors in punctuations through to the last chapter which concluded in a total mayhem with Milly’s thoughts. It had 5000 errors and many of them were intentional.Stream of consciousness as suggested by the terminology is but an internal act of undeterred flow of thinking. When reflected in narration, the written language flows unplugged without stops. Sentence endings and punctuations in the narrative are rare and often ungrammatical with misspellings as they would appear in the characters’ thoughts. Monologues, therefore, take precedence over dialogues and soliloquies. Such thoughts are sporadic and must never find an audience. They appear in the mind spontaneously and remain there for as long as the characters are engaged with the selves.Only narrators who are omniscient and omnipresent have access to those private thoughts and it is their jobs to soak them up like sponge and wring out the sponge in narrations so the reader would know exactly how they took place in the characters’ minds. As a mediator, between readers and the characters, the narrators do not interpret or intervene in such thought processes, rather allow for the narrations to be filtered through them.Having said the above, how does this definition fit Moirae? Although Moirae is an ode to a nondescript, floating population, it is nevertheless an allegory and a dream allegory at that. The story is one of persecution where innumerable nameless people are seen fleeing their villages together on a boat called the Blue Moon, to seek asylum elsewhere. However, the place in which asylum is sought is not free of danger either. And they soon find their fates hanging in the balance, once again.The narration takes place in a dream of the main character, a female protagonist by the name of Nalia. Nalia is intelligent but is a poor village girl. She sees things through her wavering dreams which the narrator follows and pens down as they appear. The only place where the narrator’s presence is felt is when she introduces her own PoV. However, those points of views have also been interjected in a dreamlike fashion so they would merge seamlessly into an already existing dreamline that Nalia is dreaming.As for the other characters, they are all conceived in Nalia’s one gigantic dream, where diverse thoughts, voices, actions and experiences have slipped. We see them through a haze of smoke-screen. The many errors littered across the novel are thus accounted for as stream of consciousness; a result filtered through this lucid dreaming. The ending of the novel is particularly dreamlike where a utopia has been painted and delivered to this long suffering, plight-ridden people. A place where spectacular new life begins.One parallelism that can be drawn between Moirae and Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is this, Heart of Darkness is a voyage just not to Africa, but into the minds of a confused peoples at the brunt of the horrific treatment by the British colonization. The chaotic, stream-of-consciousness style Conrad adopted displayed the confusion of those characters, and challenged the readers to think what the writer meant. Conrad experiments with this style, left some sentences without ending: “not a sentimental pretense but an idea;…something you can set up…and offer a sacrifice to….” (Conrad, Longman p. 2195), very choppy sentences full of holes for readers to interpret for themselves what they meant.Conrad talks of the “two women knitted black wool feverishly,” similar to Moirae where the character Nalia records her story in her knitting, in her dreaming, of the horrendous persecutions by the regime. This which substitutes Conrad’s British of “weak-eyed devil(s) of a rapacious and pitiless folly” (Conrad, Longman pp. 2198, 2199, & 2202). Like Conrad’s mind moves through a long literary monologue to convey to the reader his ideas, Nalia in Moirae does the same, interpreting perceived notions of democracy through long monologues in her knitted tales.—————————Nalia finds herself trapped in a strange and inescapable lucid dream. Danger looms ahead for her friends. Pressured out of their homes in the Lost Winds, every step threatens them with persecution and death.Taking a daring route on a treacherous sea, they seek asylum in a new land. Will they make it to their destination? Will Nalia’s dream of finding peace in Draviland become the utopia that she desperately desires, or are the dangers of this new land even worse than her home?Set in a real time, stream-of-consciousness narrative, this story takes you on a sweeping literary journey.Buy Moirae on Amazon

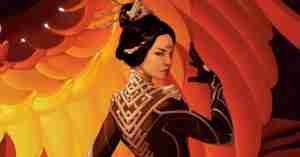

Iron Widow: Inclusive Classroom Library

Iron Widow by Xiran Jay Zhao is one of our school’s considerations for the grade nine de-streamed classroom. These are my