Friedrich Nietzsche’s Death

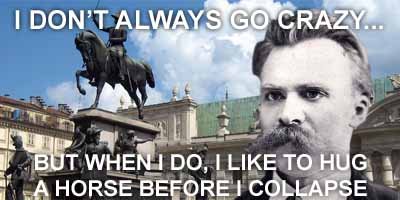

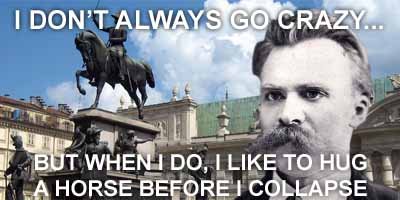

The story often told is this: Nietzsche was causing a ruckus in the streets of Turin as he made his way to the Piazza Carlo Alberto. Upon arriving, he found a man whipping a horse. Nietzsche ran to the horse and threw his arms around it, to protect the animal. At that moment, he apparently collapsed under the weight of his own philosophical beliefs.

It’s a great story about a man that was so distraught by his own philosophical beliefs that it eventually crushed him. The only problem is this: it’s most likely not true. There is no doubt that Nietzsche collapsed on January 3rd, 1889. Overbeck, who was immediately notified of what what happened to Nietzsche, logged the incident. He makes no mention of the horse, only that Nietzsche was in the throes of some kind of madness.

The story about the horse whipping came from a tabloid style newspaper called the Nuova Antologia. The article was written one month after Nietzsche’s death, on September 16, 1900 – eleven years after the event.

Adding further suspicion to this story is the statue in the Piazza itself. There is a large equestrian statue of Carlo Alberto sitting on his horse, sword drawn high, in the middle of the park, as if he might smack the horse with it. The story in Nuova Antologia seems to be based on what is in the piazza, not on any relevant testimony.

There is no doubt that Nietzsche’s actions were becoming erratic. He showed signs of mental illness throughout most of his life. Some believe that he had syphilis, though the duration of his madness indicates otherwise. There is evidence that he had cancer in his brain, which is now thought to be the cause of his death (previously, it was assumed he had a stroke). One thing is for certain: after his collapse in Turin, he was seriously mentally ill.

There are several letters written by Nietzsche shortly after January 3rd that contain bizarre ramblings. He signed the letters usually as Dionysus and sometimes as ‘the crucified one’. His mind drifted between states of psychosis, to dementia, to moments that seem similar to being in a catatonic state. During this time, Nietzsche was juggled around between a few psychiatric clinics and wards until his sister, Elisabeth, cared for him.

Elisabeth wanted to understand her brother’s work. She hired Rudolf Steiner as a tutor but Steiner gave up on this endeavor after a few months. He declared that it was impossible for her to learn anything about philosophy. This didn’t discourage Elisabeth, however, as she continue to compile and re-write his unpublished notes for The Will to Power. The work was published posthumously. Sadly, the phrase, will to power, became popular in Nazi circles. Largely because of Elisabeth, passages of Nietzsche’s work became important to the Nazi party. Nietzsche himself promoted radical individualism throughout his life. The idea of his work becoming associated with socialism in any way would have been enough to drive him to madness.

When I look back at Nietzsche’s life, I am saddened by how truly horrible it was. Though a topic for another article, from an early age onward, he suffered. There is no doubt that his circumstances led him towards nihilism. His life, and particularly his end, was an exposition of his philosophy.